Water as a Democratic Good

The question about who gets to drink water is also a question about who belongs.

The wars of the future, our parents liked to say, would be waged over water. Given the myriad ways humans have failed in their tasks as custodians of this Earth, they said, water would soon be so scarce that nations would battle not over widening their territorial expanses but over keeping their populations alive. In a sense they were early, but in another they were late.

I am speaking of the ways that water has been weaponized as an instrument of statecraft and subjugation throughout history. It may be that by the 90s, the Boomer/Gen X thing to do was to revel in newfound scientific knowledge—progress!—and the comfort of never having to confront it—mortality! How sweet it is. But what once seemed like a distant shame is quickly becoming a present reality. Today’s water battles are not over which nations have claim to the rapidly desiccating well, but over who, in a democracy, gets to drink from the abundant spring.

Water is about who belongs.

In this week’s New Yorker, I read a good essay provocatively titled “American Democracy Was Never Designed to Be Democratic.” Sure, whatever, I thought. The cynic in me finds these kinds of articles a bit tired these days, as if it should be some big revelation that a government that authorizes all manner of aggression in modern times has also eroded people’s rights since the Founding. Moreover, debates about whether the United States was founded as a democracy or not feel less worth my while when the question we are faced with today is deciding our intention about whether we want to be a democracy now. It’s far more pressing to study which people get to participate in full democracy and which are denied that access.

My interest only grew, though, as I read more. The article is more of an exploration of the origins of districting practices in the United States, including gerrymandering and its two vehicles: cracking and packing. (Cracking entails breaking up a solid voting bloc and distributing those votes to districts where they are guaranteed to be the minority; packing involves putting as many voters from one party into a single district so as to weaken their influence in others.) It traces the origin of these practices back to the negotiations of the Constitutional Convention to make the point that the system is intentionally designed to secure the representation of some in the political process at the expense of others. I realize that the point of the piece is to examine the inclusion question.

Access to water is one more way in which the state can carve out democratic and political rights. In Florida, Menand writes, it is now illegal to offer water to someone standing in line waiting to vote. The law, SB 90, bans any person, organization, or political committee from engaging in any activity that has the effect of influencing any voter. Although it may seem common sense to prohibit political parties from shouting slogans in your face through a bullhorn while standing in line to vote, this language is also sweepingly broad such that a nonpartisan organization handing out bottles of water to voters baking in the Florida sun could be found to have broken the law. (The average high in Florida climbs to 80ºF still in November.)

And it’s not just Florida. SB 90 is in part modeled after a law in Georgia that prohibits the same behavior, which has been challenged in the courts for months. Advocates have argued that laws banning solicitation in such overbroad language have the effect of discriminating against Black voters and other voters of color. Black and Latinx voters face longer wait times at polling locations, and thus a higher likelihood heat exhaustion or dehydration if they cannot receive water: A 2020 report from the Brennan Center for Justice found that Latinx voters waited on average 46 percent longer than white voters to vote, and Black voters waited on average 45 percent longer than white voters to vote. And we’re not talking about the difference between 10 or 15 minutes. Some 3 million voters are estimated to have waited longer than 30 minutes to exercise their right to cast a ballot. (Consider also that Black and Latinx voters are at higher risk for the sudden onset of symptoms from high blood pressure or diabetes, for which the most immediately available treatment is often water.) Last week, a judge declined to block this portion of the Georgia law, declaring that it’s too close to the election—which is 74 days away—to eliminate any provision in the law.

Determining who gets to access water in a country that has plenty of it is nothing short of an expression of whose lives we really value. Of course, the solution may seem easy. Just bring your own water bottle. The problem, though, is that water has a way of running out. The body demands hydration.

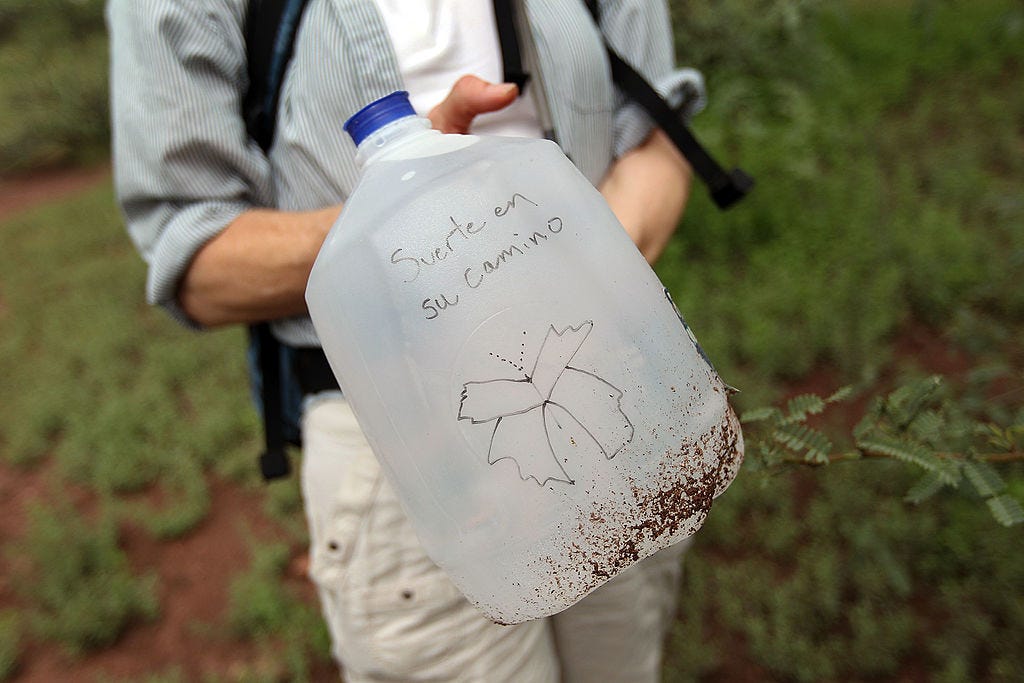

Between 2012 and 2015, the group No More Deaths scattered 31,558 gallon jugs of water throughout the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, placing them in the desert to help people who were crossing into the United States on foot. Other groups like Humane Borders set up 55-gallon plastic barrels with spigots for the parched migrants. Think of the heat. Think of the dryness in the air. Think of the sour taste of sand and death that makes its home at the back of your throat. In 2018, footage surfaced of Border Patrol agents opening the water jugs and dumping them onto the desert, which does not need it. Some of the jugs were also found pierced or destroyed, meaning the migrants couldn’t even use the containers to fill them up.

“They must hate us,” a 37-year-old migrant named Miguel told The Guardian at the time.

In the extreme cold, too, water can cause harm. November 2016 was a high point of the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock Reservation, during which thousands gathered to stop construction on an energy pipeline that Indigenous people said would poison their water supplies. They called themselves “water protectors,” rooting their resistance in Indigenous traditions. On November 18, the Morton County Sheriff’s Office released an advisory to the public urging the water protectors to disperse because of the high risk of hypothermia and frostbite. “The number one goal of all state and local officials,” they said, “is the safety of all involved in this event, including the protesters.” Two days later, however, the police deployed water cannons against the protesters, soaking them in sub-zero temperatures and a wind chill of 14ºF. A film series project “Cold Cases” documented at least 68 uses of water cannons over a 12-hour period and over 300 cases of hypothermia from the whole endeavor.

As icicles formed on the barbed wire, the very water they wanted to protect was being used against them. Do you know what accelerates the onset of hypothermia? Dehydration.

Some might feel like the comparison of a 30-minute wait in line to police violence is hard to make. The larger point here is not about the specific circumstance, but about the desperation that the political subject is made to feel by their body’s demand for something they will not be allowed obtain. Psychologically, this deprivation easily tortures you into submission. And maybe that’s the point. The New Yorker piece has this insightful line: “The scandal isn’t what’s illegal. The scandal is what’s legal.”

In Florida and Georgia and Arizona and Flint and Standing Rock, people thirst for water. I imagine they also thirst for freedom.

If you’re interested in reading more on the weaponization of water in an international context, read this report from Amnesty International on water access in Palestine:

“In November 1967 the Israeli authorities issued Military Order 158, which stated that Palestinians could not construct any new water installation without first obtaining a permit from the Israeli army. … Some 180 Palestinian communities in rural areas in the occupied West Bank have no access to running water, according to OCHA. Even in towns and villages which are connected to the water network, the taps often run dry.”

Piercing the water jugs along the border is evil. I read another Substack, The Border Chronicle, which describes the many inhumanities perpetrated by the Border Patrol in the borderlands. It's a prime example of how operating out of sight corrupts people.

Your piece also calls to mind water shortages in California, which highlight water inequalities. While lavish golf courses drink up oceans of water, the homeless struggle to get a single drink.