Frederick Douglass’ Wish for Immigrant America

“I know of no rights of race superior to the rights of humanity,” Douglass said. Whiteness, he argued, could not justify the denial of human rights.

This week, we’re diving into history. Much in the same way that the law builds on its own precedent, the future is often constrained, and predicted, by what has already been. As brutal attacks on Asian Americans mount, I am reminded of the nativism against Chinese immigrants (and Asians broadly) that cloaked the post-Civil War period at the very same time that America was trying to achieve a just Reconstruction. Douglass explicitly linked this violence to the strength of their legal rights to argue for full citizenship.

Let’s get into it.

WHEN CONGRESS ABOLISHED slavery in the District of Columbia 160 years ago this week, it couldn’t shake the idea that Black people were more than just their labor.

The District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862 had the primary purpose of abolishing slavery. But the law also ordered the Treasury to pay the enslavers up to $300 per enslaved person “in full and complete compensation” of their supposed economic loss. This government-sanctioned purchase of freedom paved the way for Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and, after the close of the Civil War, the Thirteenth Amendment. Although he had been born into slavery, Frederick Douglass witnessed and advocated for these developments from freedom.

After escaping from a Maryland plantation aboard a northbound train in 1838, Douglass became not only a fervent advocate for the abolition of slavery and the passage of the Reconstruction Amendments, but also internationally acclaimed for his writing and oratory. In 1869, with slavery abolished but the vote and equal protection not quite yet secured for all U.S. citizens, Douglass began touring the country giving a speech in which he advocated for equal rights for immigrants, too.

His fear: that we would emerge from the Civil War without understanding how its bloodshed was rooted in stubborn dehumanization.

The speech, titled “Our Composite Nationality,” was an ode to the multi-ethnic, cosmopolitan country we could become, one in which all races live in harmony. Douglass hoped that if other Americans could see the potential success of this experiment, we could move forward from our slaveholding past and reforge our national identity. In urging others to see the humanity in the stranger, he argued, “A smile or a tear has not nationality; joy and sorrow speak alike to all nations, and they, above all the confusion of tongues, proclaim the brotherhood of man.”

By that time, America was faced with a steady influx of Chinese immigrants, many of whom were sailing across the Pacific to work along the West Coast under the terms of the Burlingame Treaty of 1868. The treaty enshrined the right of Chinese nationals to migrate to the United States, but it also denied them any opportunity at naturalization. Between 1860 and 1870, the Chinese population in the United States doubled, which, as you may guess, brought about untold levels of violence against the newcomers. Even though the United States approved their migration, the government could not—or simply would not—protect them from these threats. “Already has [California] stamped them as outcasts and handed them over to popular contempt and vulgar jest. Already are they the constant victims of cruel harshness and brutal violence,” Douglass lamented.

Such violence against Asian Americans still casts a dark cloud in 2022, this time over the entire country. One year after the Atlanta shootings, violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders continues to rise: The Washington Post reports that anti-Asian hate crimes have increased by 567 percent in the past year alone. But it’s not just about the aggregate violence—the specific instances are gut-wrenching. Asian women have had to change their routines for fear of succumbing to the blows and stabs of men. Much like in Douglass’ time, the violence appears to be fueled by fear of the stranger and somber—but inaccurate and racist—predictions of an ‘invasion.’ Unlike in Douglass’ time, social media algorithms and right-wing commentators inflame those fears when they promote the view that somehow an entire category of people can be nothing more than a plague.

In his 1869 speech, Douglass was pointing to the beginning of a new (and perverse) legal innovation: the creation of a category of humans whom the law recognizes as subjects for labor extraction but not as subjects worthy of full protection. In Douglass’s words, “It was not the Ethiopian as a man, but the Ethiopian as a slave and a coveted article of merchandise, that gave us trouble.” As historian Kelly Lytle Hernández observes, the problem of slavery was not rooted in some fixed quality about the bodies of the enslaved, but rather “in the laws that organize inequitable social relations and protect the marginalization of humans.” This was the overarching lesson that Douglass sought to apply from his own experience while enslaved to the immigration question: that restrictionism at its core necessitated “strategies of exclusion that African Americans were battling against in the years after the Civil War in their struggle to achieve full emancipation,” according to Lytle Hernández.

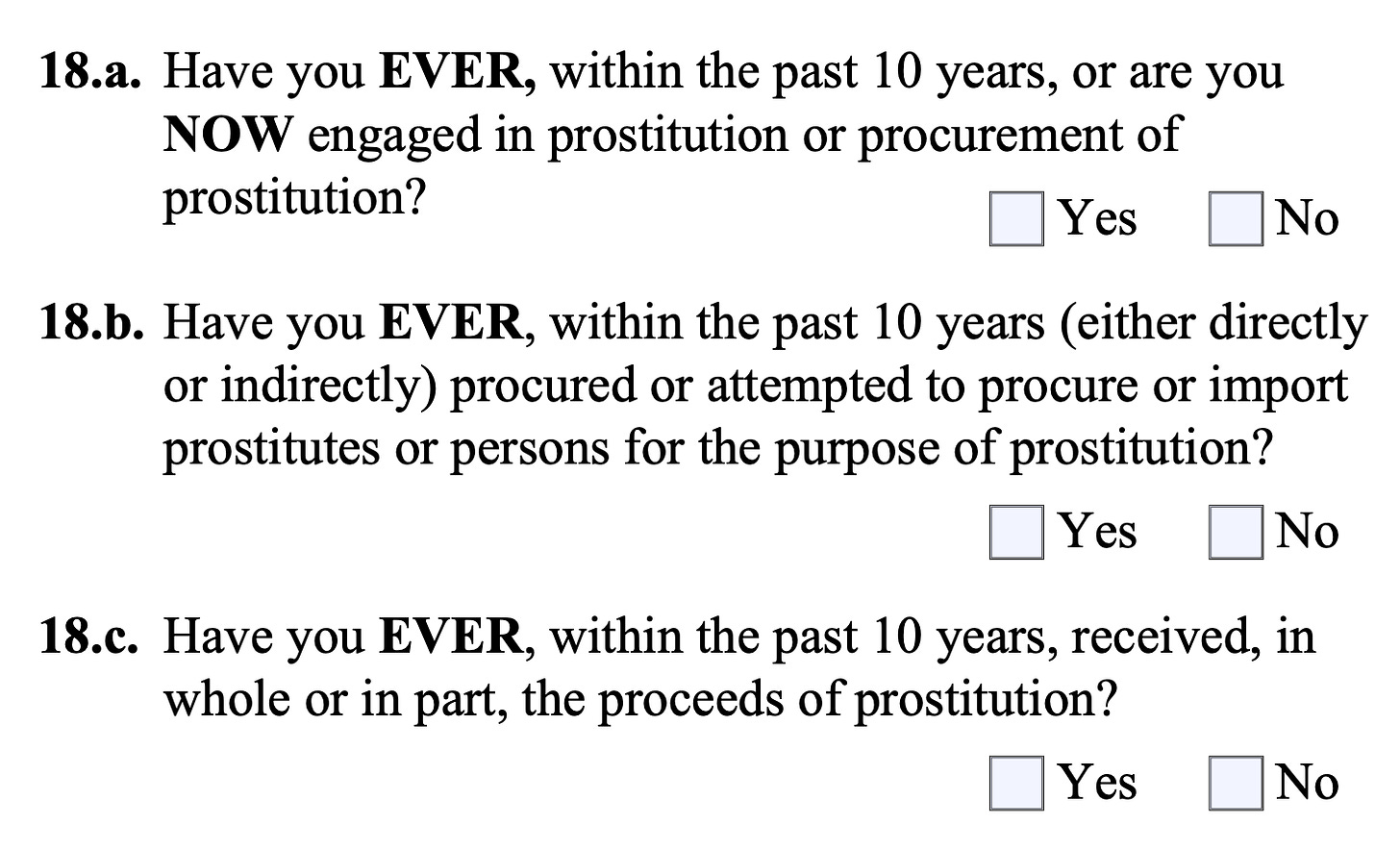

He was right. In the years that followed, Congress passed a slew of restrictions on immigration, targeting all manner of characteristics like intellectual disabilities or chronic illnesses as well as behaviors and beliefs like polygamy and anarchy. (These categories have been immortalized in our ever-inquisitive immigration forms to this day.) In 1882, Congress excluded all Chinese laborers from the country. The courts also provided the legal scaffolding on which these limits could sit, making all immigration (and immigrant) control an incident of absolute national sovereignty in the Chinese Exclusion Cases. By 1924, Congress had shut the door on virtually all Asian immigration as well.

Racial control in general also opens up the door to social disciplining. When the state seeks to control behavior without overtly outlawing the color of one’s skin, the behaviors and traits associated with that race will be excised. The Page Act of 1875, for instance, proscribed migration for “lewd and immoral purposes” and the entry of women to perform sex work. That dragnet ended up catching all women, who were subjected to abusive examinations and interrogations at Angel Island. We know because the women scribbled poems on the wall: “Sitting alone in the customs office, / How could my heart not ache?”

The harm of these categories remains immortalized in our ever-inquisitive immigration forms to this day. Boxes that begged to be ticked.

In “Our Composite Nationality,” Douglass rejected the idea that immigration could depend on something as unchangeable as race. “There are such things,” Douglass said, “as human rights”:

They rest upon no conventional foundation, but are external, universal, and indestructible. Among these, is the right of locomotion; the right of migration; the right which belongs to no particular race, but belongs alike to all and to all alike. It is the right you assert by staying here, and your fathers asserted by coming here. It is this great right that I assert for the Chinese and Japanese, and for all other varieties of men equally with yourselves, now and forever. I know of no rights of race superior to the rights of humanity.

Douglass’ conception of migration was ahead of his time. (The revered Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for instance, was not signed until 1948.) Even as many Black U.S. citizens still had never cast a vote in federal elections, Douglass used that conception to argue that immigrants should be allowed to come here, to become citizens, to vote, and to hold office.

Race and slavery thus have an inextricable connection to immigration and legality. Slavery set a precedent by which people could be legally recognized as agents to produce ever-growing profits but had diminished human rights. In addition to the daily corporal punishment they suffered, enslaved people were forced to inhabit a perpetual undercaste with no path to full citizenship.

Douglass warned the country that this fate could befall the next racial category and that white citizens should not get to become “the owners of this great continent to the exclusion of all other races of men.”

The function of the law is often to organize society—and in so doing, to exclude. But even as it tries to create a homogenous nation, the law can be constrained in its ability to force actual outcomes on the ground. Those who assert their existence here by simply staying are posing a direct challenge to racist laws. As their roots to their communities deepen, their livelihoods and the roles they take on in society become impossible, even for the law, to deny.

And in the face of virulent racism, it’s often those who have personally known the helplessness of being dehumanized who come to defend us.

As ever, we keep us safe.

***

That’s all for this week. Thank you for reading.

If you liked this essay, I hope you’ll subscribe, leave a comment and share this newsletter with your friends.

Wow!! What an amazing and insightful read.